The impact of sales tax legislation on ecommerce

Understanding ecommerce & internet sales tax bills

When Montgomery Ward issued its first catalog in 1872, sales tax wasn’t yet a twinkle in the eye of lawmakers. The first local sales taxes were adopted in the 1930s in response to reductions in government revenue. It only took a few decades for the complexities of sales tax to garner congressional attention. In 1965, a congressional report noted that the existing system of state taxation affecting interstate commerce "…works badly for both businesses and the States." From the beginning, the aims of state government and remote sellers ran counter to one another.

On the one hand, states sought to maximize revenue by compelling these vendors to collect sales tax. On the other, remote sellers often resisted these requirements, invoking federal rules protecting interstate commerce. The issue centered on definitions of nexus (physical presence within a taxing jurisdiction that triggers sales tax collection obligations) set forth in prior rulings. In the 1990s this conflict culminated in the State of North Dakota filing a lawsuit claiming that the Delaware-based retailer Quill Corporation owed sales tax.

The case became a referendum on taxing requirements for remote sellers. North Dakota courts ruled in support of compelling Quill Corp to pay, and then another state court overruled. The lawsuit made its way to the State Supreme Court of North Dakota, which concluded that the Quill Corporation had no nexus and no related sales tax obligation.

But the case didn’t stop there.

When the Supreme Court ruled on remote sellers

In 1992 after more wrangling at the state level, the case rose to the U. S. Supreme Court (The Quill Corp v. Heitkamp, 504 U.S. 298 (1992) (hereafter Quill), resulting in a ruling that would guide the collection and remittance of sales tax by remote sellers for decades.

Though the U.S. Supreme Court determined that the nature of Quill Corp’s activities within North Dakota meant that the imposition of sales tax on the company was fair, requiring collection and remittance of the tax created an "undue burden" on interstate commerce. The Court findings highlight the complex burden of ensuring constitutionality from the perspective of the Commerce Clause of the U.S. Constitution (not interfering with interstate commerce), and the Due Process Clause (ensuring the fundamental fairness of government), particularly when they run counter to one another. For example, "...while a state may, consistent with the Due Process Clause, have the authority to tax a particular taxpayer, imposition of the tax may nonetheless violate the Commerce Clause." In other words, companies engaged in interstate commerce can be required to charge sales tax, as long as it does not substantially interfere with that commerce.

It is this complexity, combined with rapid change at the local, state, and federal levels that poses problems for remote sellers, particularly ecommerce.

Definitions of nexus between states are often so incongruous that many ecommerce retailers understandably throw up their hands and assume that they don’t have to collect and remit sales tax in municipalities in which they don’t have physical presence. By doing so they unknowingly increase their risk of audits and associated penalties.

The value of a deep understanding of sales tax nexus

To address these complexities, the U.S. Supreme Court clarified that only those companies with "significant physical presence," or "nexus" in a state would be required to collect sales tax there. This so-called "bright line" definition established physical nexus as the prevailing standard by which sales tax requirements for remote sellers were measured. In effect, this resulted in an assumed tax exemption for remote sellers without this physical presence.

This assumption is faulty and here are two reasons why:

- State taxing authorities are forever defining and redefining the activities that cause nexus that are not explicitly mentioned in Quill. See Nexus Quiz sidebar.

- To compound the confusion, so-called "Home Rule" states such as Colorado, Idaho, and Louisiana, can delegate taxing authority (including rulemaking regarding nexus) to local jurisdictions.

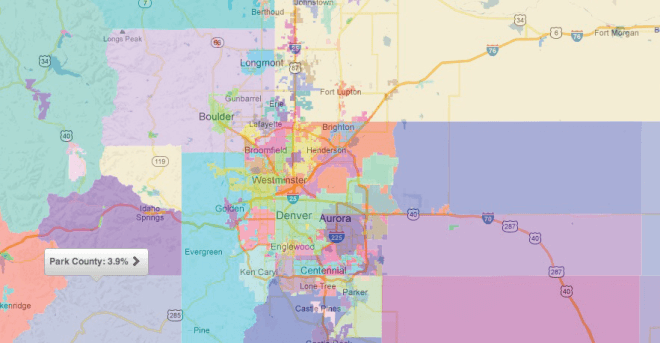

The State of Colorado: Each color represents a different taxing jurisdiction

This map shows taxing jurisdictions within the State of Colorado. Considering that each jurisdiction could have different taxability rules as well as tax rates, the complexity is somewhat daunting. Unfortunately this is just the tip of the iceberg.

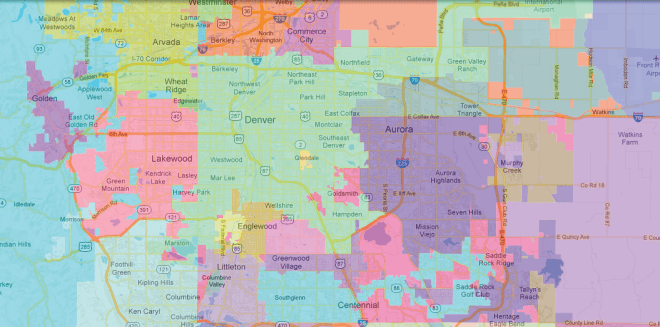

Further Down the Rabbit Hole: The city of Denver

This map shows the greater Denver metropolitan area with even more taxing jurisdictions and attendant rates and rules. This makes it essentially impossible to consistently determine an accurate sales tax rate and to manage the frequent changes to both jurisdictions and taxability requirements without some form of powerful automation.

Determining accurate taxability encompasses layer upon layer of complexity. If online retailers could use Quill to quickly calculate where they have nexus (a significant physical presence within the state) and those states where they don’t, determining nexus would straightforward.

Alas, this is not the case. Determining nexus for ecommerce and remote sellers only tells a small part of the story. The calculations and analysis needed to measure true taxability at the product and service level require more time and expertise than most companies possess. In other words, using Quill to assume exemption is a very common mistake, especially given the changes that are coming at the federal level.

These changes stem from the original ruling, in which the High Court calls upon Congress to revisit the issue of physical nexus and potentially overturn Quill. So while states are not allowed to impose nexus legislation in conflict with federal regulations, they are allowed to define nexus in ways they deem appropriate (as long as they don’t contravene Quill). In other words, remote sellers are required to follow a myriad of rules far more complex than mere physical presence determinations.

With over 11,000 taxing jurisdictions in the United States, "each with its own rules and ability to conduct audits, compliance with each is not a trivial task."

Maintaining a level playing field for all retailers

Quill clarified the tax obligations of remote sellers and defined physical nexus in order to reduce the burden of collecting and remitting tax on remote sellers. In turn, this defined tax liability without hindering interstate commerce. Justice White’s dissenting opinion argued that bright-line nexus benefited remote sellers. Free from being required to collect sales tax, these entities could charge lower prices than their brick-and-mortar competitors. This inequity ignited debates regarding marketplace unfairness. Whatever the cause, issues of fairness and perceived inequity penetrate tax policy discussions at every level.

Fueled by this perceived inequity, common arguments levied against online retailers include claims that their tax advantage allows them to:

- Drive mom-and-pop operations out of business

- Transfer tax burden to brick-and-mortar stores

- Deprive state and local jurisdictions of much needed sales tax revenue

On the flip side, ecommerce analysts and online retail trade groups argue that ecommerce stimulates the economy by uncovering previously untapped markets, creating more affordable options (and a freer market) for the consumer. Defenders also note that shoppers go online not to save on sales tax, but for greater convenience and a larger selection. Nevertheless, the perception of unfairness persists. Lost sales tax revenue attributed to online retail has been the lightning rod for heated opinion-making on both sides of the issue.

In 2011, states collected over $234 billion dollars in sales tax revenue (31% of total tax revenue collected). Other than income tax, state and local jurisdictions rely most heavily on sales tax to support schools, infrastructure, public-safety or the like. The loss of sales tax revenue associated with online retail has become increasingly important in the face of declining state revenues, and in light of the fiscal crisis of the past few years. Following the market crash of 2008, many states faced a looming fiscal crisis, the likes of which had not been seen in a generation. Between 2008 and 2009, states faced dramatic reductions in overall revenue as well as dramatic budget shortfalls.

At a time when states are recovering from "the great recession" there is a heightened awareness of uncollected revenue (especially in the amounts associated with online retail exempted by Quill). Efforts to estimate revenue losses associated with the remote seller exemption are varied. However, a prominent University of Tennessee study is the most commonly cited data source. According to the study lost revenue associated with ecommerce will be $11.4 billion in 2012. When catalog, phone, and all other interstate transactions are included, the Streamlined Sales Tax Governing Board estimates that number is closer to $23 billion annually.

States take action to simplify sales tax compliance

In 1991, The National Governor’s Association and the National Conference of State Legislatures formed the Streamlined Sales Tax Governing Board to "…simplify and modernize sales and use tax administration in order to substantially reduce the burden of tax compliance." States that voluntarily participate can petition for full membership by meeting specific requirements to simplify tax administration.

To qualify for membership, states must comply with the Streamlined Sales Tax User Agreement (SST). Twenty-four states to date are full members, and a number of others are on their way to full membership. States in compliance with the SST follow strict guidelines including the utilization of technology to modernize and actualize efficiency in sales tax administration.

With respect to nexus and remote seller sales tax rules SST specifies that, "…each SST member state is authorized to require all sellers not qualifying for a small seller exception to collect and remit sales and use taxes…" This authorization is consistent with language in proposed current federal legislation.

Federal legislation and the surprising support of former adversaries

Each of the three pieces of federal legislation before Congress require states to meet certain requirements in order to require remote sellers without physical presence to collect sales tax. Both the Main Street Fairness Act and the Marketplace Fairness Act allow states to require remote sellers without physical presence to collect sales tax if they join the Streamlined Sales and Use Tax Agreement (SST).

Each of these bills also proposes a "small seller" sales tax exemption, allowed even when businesses have physical nexus. For a summary of the exemption for each bill see sidebar.

For nearly a decade, Amazon.com and other ecommerce leaders fought remote seller sales tax obligations by invoking Quill. Amazon’s legal battles against paying sales tax in states where they did not have nexus are legendary. Amazon’s fight against collecting sales tax in California was so costly (over $5 million), some claimed the company effectively high-jacked the legislative process. In 2011 however, Amazon appeared to shift its approach. When news outlets began reporting that Amazon was in the process of negotiating a sales tax agreement within the same state, many were shocked. Others marked it as the beginning of a wholesale shift in requirements around sales tax and online retail.

In Governing magazine, Paul Misener, Amazon’s vice president of global public policy, stated that "Federal legislation is the only way to level the playing field for all sellers. [T]he only way for states to obtain more than a fraction of the sales tax revenue that is already owed, and the only way to fully protect states’ rights." Since 2010, some states began requiring Amazon and other remote sellers to collect sales tax. These states include New York, Pennsylvania, and the one making the headlines, California. Changes in sales tax rules have prompted observations that the days of Quill exemptions are numbered, especially when coupled with developments at the federal level.

Why would an online retailer, previously adamantly against collecting sales tax, now be one of the most avid supporters of federal legislation in favor of it? More importantly, what does it herald for other online retailers? Many argue that once courts began ruling in favor of states claiming Amazon owed sales tax, the tides turned irrevocably.

In late 2011, early 2012, Amazon leadership moved to accept the inevitable and agreed to begin collecting sales tax. For each of the deals struck with states, there were ripple effects that were felt across the world of ecommerce. While no one can predict what will happen with sales tax, it is clear that more local and state jurisdictions are considering requiring more remote sellers to collect sales tax in 2013.

Whatever happens, the only certainty is that changes will continue, and the attention on the issue of uncollected revenue will grow. These factors tend to bolster the efforts of the organizations supporting federal changes to Quill. Of the host of bills proposed during 2012, the Marketplace Fairness Act has bipartisan support in the Senate, and has been endorsed by organizations ranging from Amazon and Wal-Mart to the National Governors Association to the United Auto Workers.

How can ecommerce businesses address sales tax challenges?

Even if the debates about Quill and marketplace equity are sorted out, the difficulty of determining multi-jurisdictional sales tax obligations still seems to require a crystal ball and an army of accountants. The best solution for companies of all sizes is to utilize external resources with specialized expertise and technology.

Just as companies outsource and automate payroll management and other requirements that are extraneous to their core business, automating sales tax is an affordable, efficient way to meet the increasingly complex challenges associated with multi-jurisdictional and remote seller sales tax compliance.

There are multiple providers of outsourced sales tax services. In the ecommerce arena, a dynamic online solution that provides highly accurate and instantaneous results is the only viable answer.

Save time and money by automating sales tax management

As this research brief establishes, sales tax is an incredibly complex issue, and the ability to utilize manual systems is no longer feasible.

Ecommerce entrepreneurs frequently grapple with the choice between efficiency and expediency, all while juggling the realities of an increasingly complex business environment. When it comes to dealing with sales tax, ecommerce merchants often hold erroneous opinions such as:

- Outside the state where I’m located, I don’t have to worry about sales tax

- I only need to know and collect one tax rate in additional states where I have operations

- This company has been doing it this way for years so there is no need to change

Ironically, the entrepreneurial energy and technical savvy used to start and maintain a successful ecommerce business often don’t carry through to internal daily operations. Rather than using technology to fulfill sales tax obligations, ecommerce businesses rely on outdated manual approaches. Business owners often assume they can take care of sales tax themselves.

Whether it’s dealing with online sales tax collection, sales tax collection at a physical location, or both, AvaTax takes the stress and guesswork out of sales tax. Maintained by a staff of sales tax and technology professionals who track rates, rules and changes across thousands of taxing regions, you can feel confident you are collecting the right amount of sales tax on every transaction.

Reduce tax risk

Increase the accuracy of your tax compliance with our cloud-based tax engine and tax research services.